Infrastructure Finance for the Public Good: How Asset Recycling Can Untangle the New York MTA’s $50 Billion Debt Load

Systematic infrastructure underinvestment – a $2.6 trillion ‘gap’ – and accelerating climate change have become facts of life in the United States. Though typically attributed to politics, this Article posits the circumstances as a market disequilibrium rooted in an interplay between unique dimensions of infrastructure and distinctive features of the U.S. approach. Legislative action, including the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, is insufficient to overcome these long-standing challenges.

Based on a broad, global study of effective approaches to infrastructure finance, as well as a multi-disciplinary analysis of the economics, engineering and finance literature, this Article proposes addressing the U.S. infrastructure disequilibrium through asset recycling. Asset recycling is an innovative strategy, pioneered in Australia, premised on: (i) monetizing existing, government-owned infrastructure; and (ii) reinvesting the proceeds in development of new assets, which can be ‘recycled’ again, creating a virtuous cycle on a debt-neutral basis.

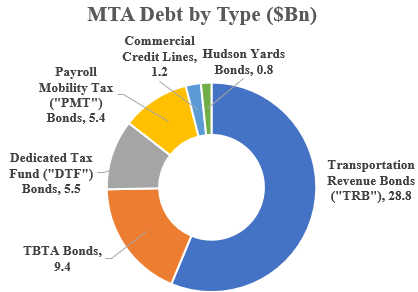

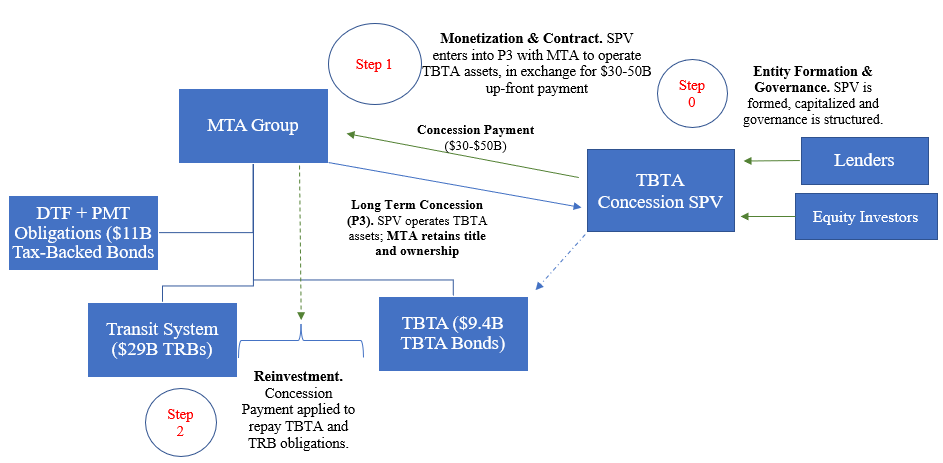

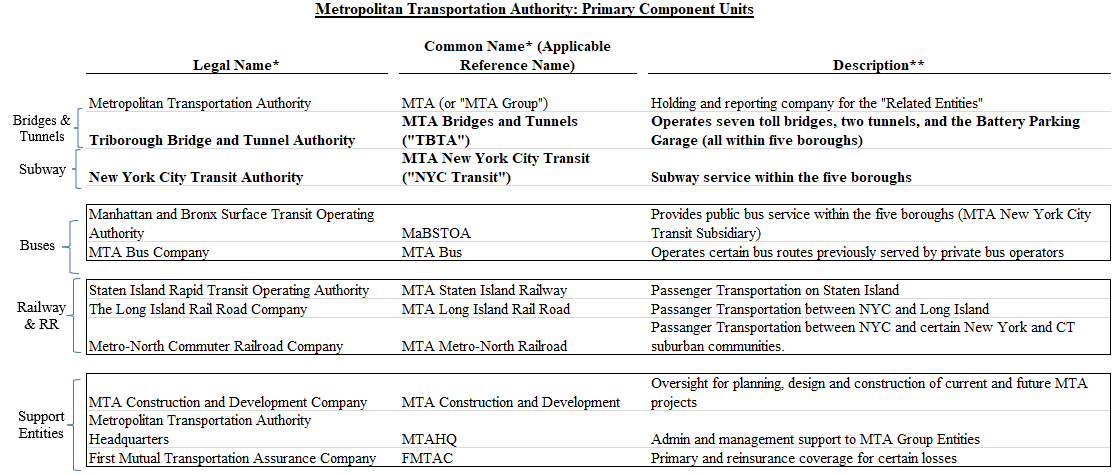

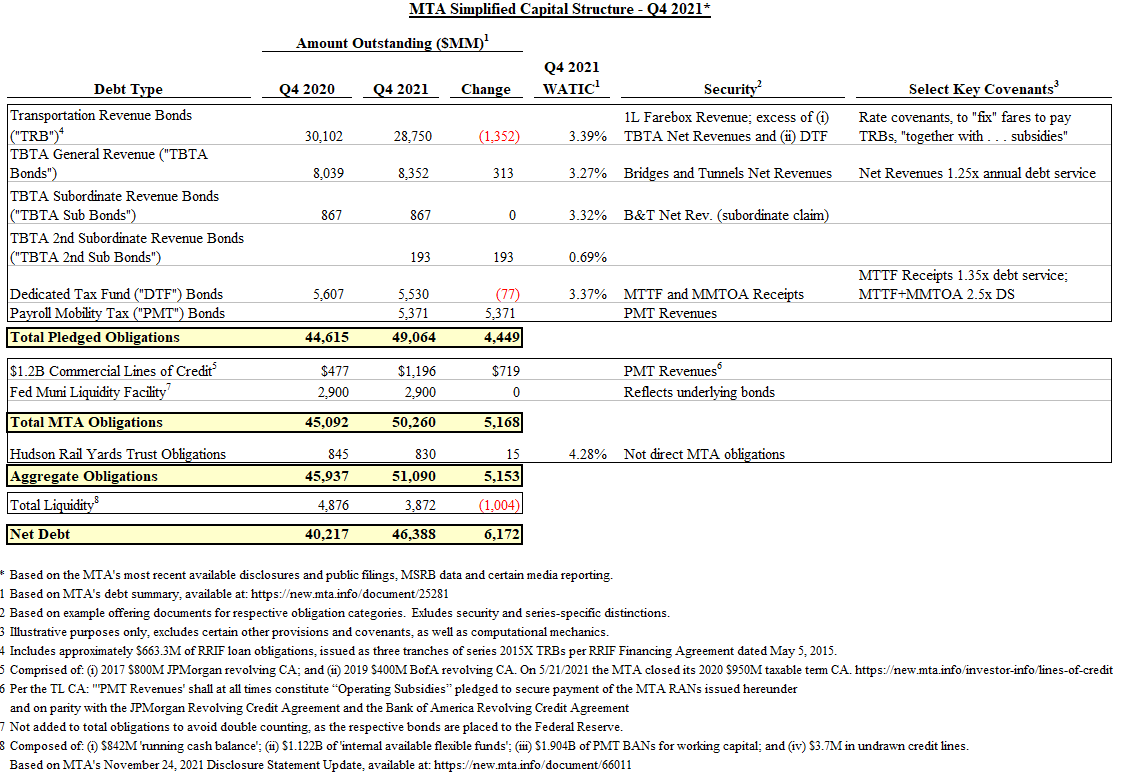

The Article illustrates this approach through a detailed, empirical case study of the New York MTA, the nation’s largest transit agency. The MTA has over $50 billion of debt, COVID-19-related losses exceeding $20 billion and bond covenants, as well as state law explicitly prohibiting bankruptcy. The analysis finds that monetizing solely the MTA’s bridge and tunnel assets (but not the subway) through a long-term concession could, conservatively, generate $33 to $53 billion – sufficient to repay the majority, if not entirety, of the MTA’s obligations, giving it the wherewithal to build the sustainable infrastructure that New York deserves.

Beyond the mechanics and empirics, the underlying principles – leveraging private capital, coupled with robust oversight – have far broader implications, as asset recycling is estimated to represent a $1.1 trillion opportunity. The Article concludes with a discussion of normative and policy considerations, as well as areas for future research, including multi-stakeholder governance frameworks for imperfect public goods, ESG-based contractual mechanisms and the interplay between infrastructure policy and climate change, with an emphasis on broad-based social and allocative equity.

Introduction

“If I…took you to LaGuardia Airport in New York, you must think I must be in some third world country,” President Joe Biden once observed upon entering the financial capital of the world’s largest economy.1Marc Santora, Some See Biden’s ‘Third World’ Description of La Guardia as Too Kind, N.Y. Times (Feb. 7, 2014), https://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/08/nyregion/some-see-third-world-as-too-kind-for-la-guardia.html [https://perma.cc/4THK-GSSA]; cf. Dana Varinsky, Donald Trump Called LaGuardia Airport ‘Third World’—Here’s the Design That Will Transform It, Bus. Insider (Sept. 27, 2016, 2:12 PM), https://www.businessinsider.com/trump-laguardia-airport-redesign-2016-9 [https://perma.cc/5YXT-2MRV]. But see infra notes 125-32 and accompanying text (describing public-private partnerships to revitalize LaGuardia and JFK airports).

According to a recent Council on Foreign Relations report, “U.S. infrastructure is both dangerously overstretched and lagging behind that of its economic competitors, particularly China.”2James McBride et al., The State of U.S. Infrastructure, Council on Foreign Rels. (Sept. 20, 2023, 11:30 AM), https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/state-us-infrastructure [https://perma.cc/6KV5-97FH] (hereinafter, “State of U.S. Infrastructure”).

With a perplexing enthusiasm, the American Society of Civil Engineers determined that “[f]or the first time in 20 years, our infrastructure GPA is a C-, up from a D+,” with a $2.6 trillion ‘investment gap.’3 Am. Soc’y of Civ. Eng’rs, 2021 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure (n.d.), https://infrastructurereportcard.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/National_IRC_2021-report.pdf [https://perma.cc/6YRQ-UXNQ].

Recent legislative efforts, including the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (“IIJA” or “2021 Infrastructure Act”) and subsequent legislation, offer a starting point but are unlikely sufficient to comprehensively address the problems.4Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Pub. L. No. 117–58, 135 Stat. 429 (2021).

Policy is conceptualized broadly but experienced locally. Roads, public transit, water and electricity have an extraordinary impact on our quality of life. However, we don’t think much about those things unless they stop working.

The socio-economic importance of infrastructure, and the United States’ chronic underinvestment and neglect toward it, have been thoroughly documented in the economics and engineering literature as well as the media.5See supra notes 1-3; see also infra notes 9-12, 39-41, 96, 177-78 and accompanying text.

However, these issues have been surprisingly under-researched in the legal scholarship.

This Article aims to bridge that gap through a multi-disciplinary, empirical approach, coupled with a global perspective. It is organized in four parts.

Part I introduces the salient problem – the ‘market’ for infrastructure finance is persistently broken, impairing our economy, quality of life and ability to address climate change – and analyzes the underlying causes. The Article posits that the disequilibrium goes beyond politics, driven by a combination of infrastructure’s unique economic attributes, and exacerbated by distinctive features of the U.S. approach. Though the U.S. typically views itself as private sector-centric, it takes a meaningfully different approach with respect to infrastructure – emphasizing a government-provision model with a federalist delegation of responsibility to the state level, where the majority of infrastructure spending occurs.6See infra Part I.B.3.

In contrast, other countries have over time incorporated more private sector involvement, adopting ‘hybrid’ models to drive better outcomes – and illustrating the range of options. Based on that holistic, global framework, Part I previews the core proposal: asset recycling.

Asset recycling is an innovative strategy, pioneered in Australia, premised on a two-phase process: (i) transitioning existing, mature infrastructure assets to a public-private-partnership (but not a privatization); and (ii) using the proceeds to finance new projects. As a result, the government develops more infrastructure on a debt-neutral basis. The potential value creation is estimated to exceed $1.1 trillion.7See infra notes 109-10.

In contrast, the IIJA will fill only 18.2% to 22.4% of the infrastructure ‘investment gap.’8For a detailed analysis, see Lev E. Breydo, Inequitable Infrastructure: An Empirical Assessment of Federalism, Climate Change and Environmental Racism, 102 N.C. L. Rev. 1035, 1041 (2024).

Parts II and III contextualize and quantify these issues through a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary case study of the New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority (“MTA”), leveraging the legal, financial, economic and engineering literatures.9See Edward Glaeser & James Poterba, Economic Perspectives on Infrastructure Investment 6 (2021), https://www.economicstrategygroup.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/GlaeserPoterba_071421.pdf [https://perma.cc/K4F4-VKGT] (observing a “collision of paradigms” between engineering and economics with respect to infrastructure, noting that “[u]nlike engineers, who are often asked what it will cost to build a bridge but not asked to measure its benefits, economists are rarely asked to determine the cost of a bridge” but often asked about the cost-benefit analysis).

Part II focuses on the MTA and its challenges; Part III details application of asset recycling.

The MTA was selected, in part, because the scale and acuity of its challenges – a debt load exceeding $50 billion, a long-delayed $51.5 billion climate investment program, and “no bankruptcy” bond covenants – crystalize the necessity of innovative solutions. At the same time, the MTA, in many ways, also represents a microcosm of issues plaguing infrastructure policy nationwide, including transit systems from Boston to Chicago and San Francisco burdened by eerily similar woes,10See infra notes 147 and 223.

an “increasingly unreliable” electric grid 11Katherine Blunt, America’s Power Grid Is Increasingly Unreliable, Wall St. J. (Feb. 18, 2022, 10:06 AM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/americas-power-grid-is-increasingly-unreliable-11645196772.

and failing water systems from Michigan to Mississippi.12Melissa Denchak, Flint Water Crisis: Everything You Need to Know, NRDC (Oct. 8, 2024), https://www.nrdc.org/stories/flint-water-crisis-everything-you-need-know#sec-summary [https://perma.cc/TV77-8UPL] (“In Flint, nearly 9,000 children were supplied lead-contaminated water for 18 months.”); Alyssa Lukpat, Jackson Water Crisis: Mississippi Capital Residents Have Little to No Drinking Water. Here’s Why., Wall St. J. (Aug. 31, 2022, 11:54 AM) https://www.wsj.com/articles/jackson-mississippi-water-crisis-explained-11661877514?cx_testId=3&cx_testVariant=cx_2&cx_artPos=1&mod=WTRN#cxrecs_s.

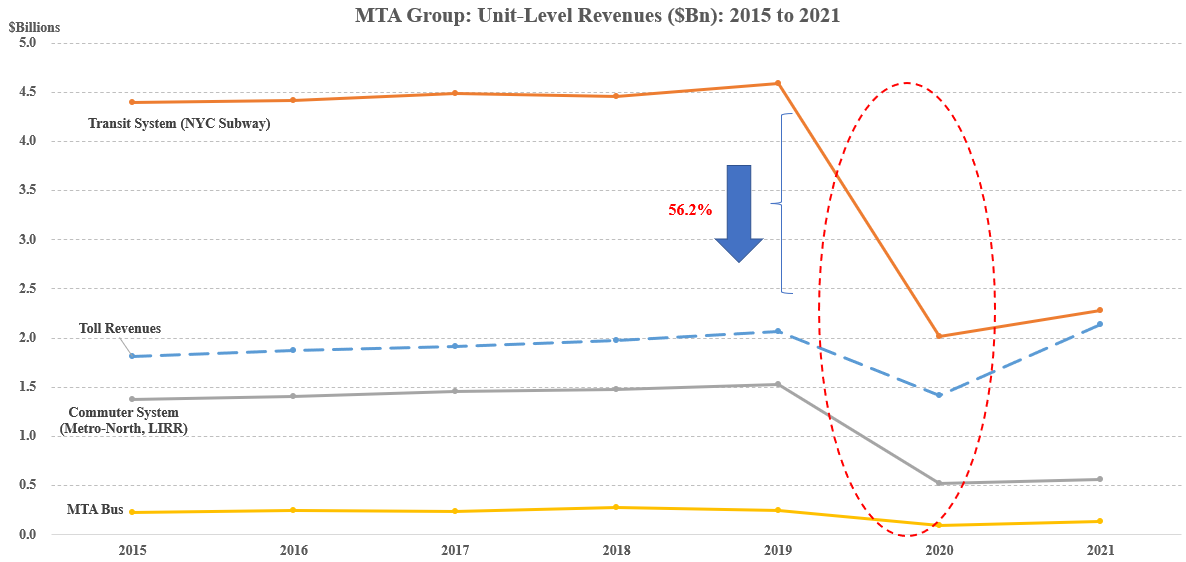

Particularly for public transit, the aftereffects of the Covid-19 pandemic have rendered dull, long-standing pain into a far more acute ailment, closer to a broken arm.

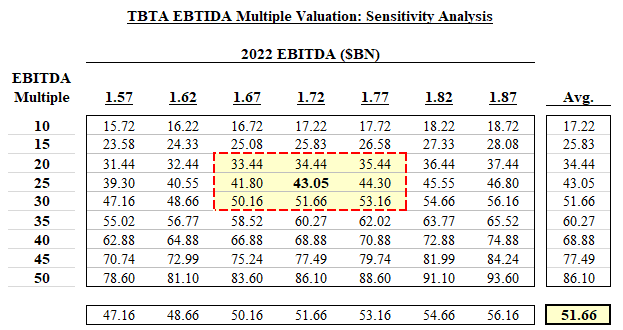

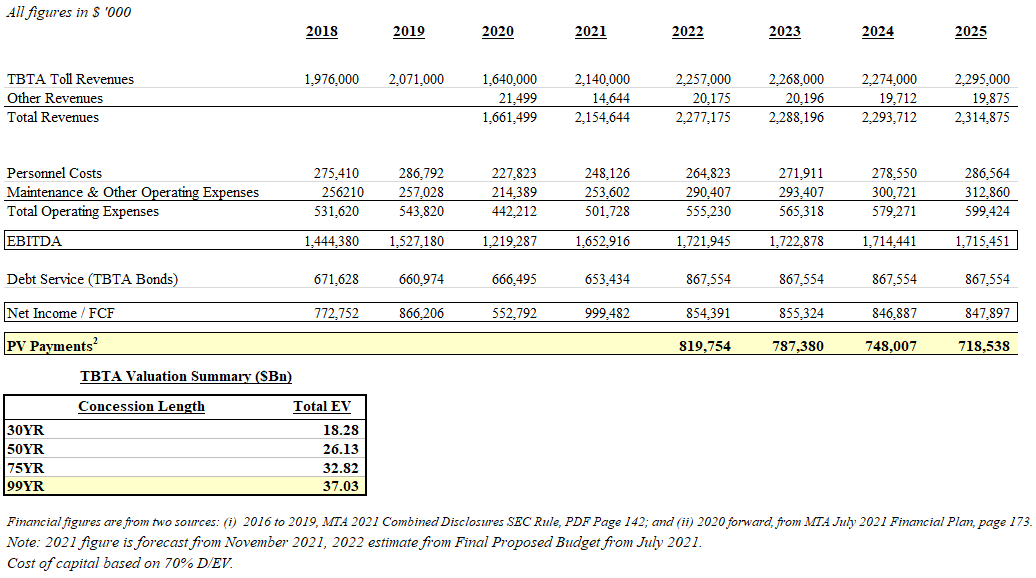

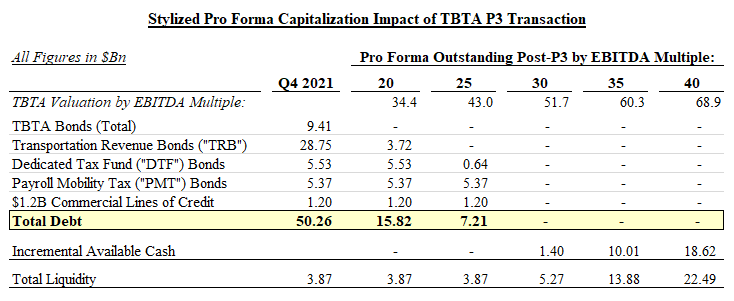

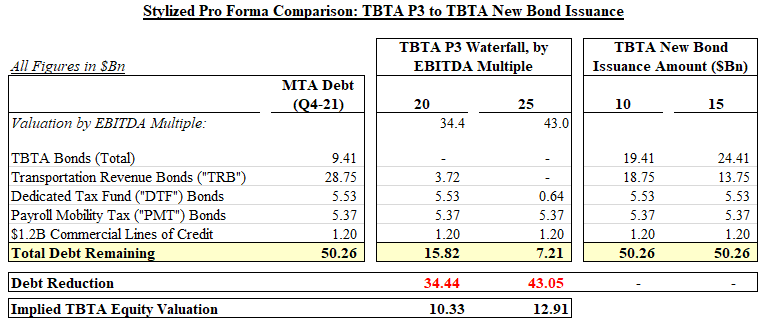

Part III empirically illustrates why a tailored asset recycling strategy presents a highly attractive avenue for addressing the MTA’s predicaments. Based on a thorough financial analysis as well as extensive market research, the Article estimates that a concession (distinct from a sale) for just the MTA’s bridge and tunnel assets could, conservatively, generate between $33 and $53 billion (and potentially up to $62 billion) in proceeds, sufficient to repay a majority, if not the entirety, of the MTA’s debt – giving it the wherewithal to invest for the future.13As discussed before, the analyses in this Article are as of late 2021 (when this research was conducted) and reflect then-prevailing market conditions and financing rates, including term structure. Correspondingly, the results of certain analyses may differ today based on evolving interest rate conditions and assumptions which are subject to change. See infra Part III for further discussion.

Part III concludes by detailing the integrative value creation from asset recycling, as well as distinctions between the proposed approach and ‘privatization,’ as the term is commonly understood. Though the empirics are MTA-specific, given similar challenges facing infrastructure nationwide, the proposal has applications and implications well beyond New York.

Part IV explores normative dimensions and policy considerations. First, it outlines key factors for implementing asset recycling, including asset selection, governance and contractual structure, with provisions tied to environmental, social and governance (“ESG”) metrics. Second, it discusses governance frameworks for imperfect public goods, such as infrastructure, finding corporate-centric approaches imprecise, and recommending application of broader multi-stakeholder models. Finally, it discusses the interplay of infrastructure and climate change, emphasizing that allocative equity and socio-economic justice must be at the heart of infrastructure policy.

I. Infrastructure Finance, Ownership & Control

Understanding the challenges facing U.S. infrastructure generally, and the MTA specifically, requires some background on how these types of assets are financed, operated and governed.

Infrastructure financing and ownership structures exhibit significant variation across jurisdictions worldwide.14McBride et al., supra note 2.

Some nations, like Australia and Japan, are relatively open to private sector involvement and investment in infrastructure. Others, particularly in Europe, take something of a middle ground. The U.S., in contrast, emphasizes public sector ownership and financing of infrastructure. However, the U.S. approach has varied over time, with the private sector previously playing a larger role – and more recently there have been growing examples of U.S. private sector involvement.15See infra Part II.C. As discussed in infra Part II.C., there is also notable heterogeneity in approach based on asset type.

The diversity of approaches illustrates a salient point: there is no ‘right’ answer,’ and more than one option.

This part of the Article sets the stage for the broader discussion. First, it introduces the salient problem – a persistent breakdown in the ‘market’ for infrastructure finance – and describes the why, focusing on distinctive aspects of the U.S. public sector-centric model. Then, it contextualizes the policy proposals through analysis of global approaches, finding increasing prevalence of ‘hybrid models.’ Finally, the discussion previews the asset recycling proposal and contrasts the associated policy dimensions with the 2021 Infrastructure Act.16Certain aspects of this discussion are reiterated, further detailed, and expanded upon in a subsequent follow-on Article. See Breydo, supra note 8, at 1042.

A. Background & Economic Foundations

The ‘market’ for infrastructure exhibits persistent disequilibria, impairing our economy, quality of life and ability to address climate change. Some of the challenges are inherent to infrastructure; others, as discussed below, are arguably exacerbated by America’s approach.

1. Taxonomy

Though a commonly used term, the definition of “infrastructure” is surprisingly complex and seemingly amorphous.17 . See Brett M. Frischmann, Infrastructure: The Social Value of Shared Resources 3-5 (2012) (defining “infrastructure resources” as “shared means to many ends.”); see also Glaeser & Poterba, supra note 9, at 185 (noting “[t]he term ‘infrastructure’ is a relatively recent addition to our national vocabulary, and its meaning has evolved over time.”); Infrastructure, Black’s Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019) (noting “standard” definitions of infrastructure); Infrastructure, Merriam-Webster Dictionary Online, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/infrastructure [https://perma.cc/S9NZ-ZK8F] (last visited Oct. 11, 2024); William Morris & Mary Morris, Morris Dictionary of Word and Phrase Origins 309 (2d ed. 1988) (providing a historical account of how the term’s meaning has evolved).

Taxonomically, in simplest terms, it can be grouped into two categories: (i) ‘traditional’ (‘hard’ or ‘economic’) infrastructure and (ii) non-traditional (‘soft’ or ‘social’) infrastructure.18This framework reflects a ‘classical’ economic perspective. It is, by intention, simplified to present a complex issue for relatively circumscribed purposes in this Article. It excludes certain categories, like digital infrastructure, such as AWS and cloud providers (telecommunications includes the ‘hard assets’ enabling digital services, but not the services themselves). Some scholars also taxonomize infrastructure along two dimensions: (i) between economic and social, and (ii) between services (‘soft’ infrastructure) and assets (‘hard’ infrastructure); see Mark Dyer et al., Framework for Soft and Hard City Infrastructures, 172 Urb. Design & Plan. 219, 219-22 (2019).

This distinction arguably explains much of the politicized debate around the recent Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.19See also supra note 4. Compare Jim Tankersley & Jeanna Smialek, Biden Plan Spurs Fight over What ‘Infrastructure’ Really Means, N.Y. Times. (June 24, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/05/business/economy/biden-infrastructure.html, with Editorial Board, A not so Grand Infrastructure Deal, Wall St. J. (July 29, 2021, 6:47 PM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-not-so-grand-infrastructure-deal-senate-democrats-republicans-11627597534.

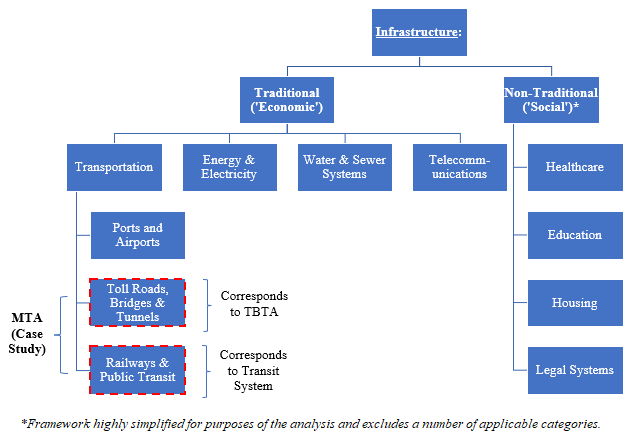

Figure 1. Infrastructure Taxonomy

For our purposes, we can think of infrastructure as “shared means to many ends” which do not directly produce goods or services, but provide the “underlying framework” or “foundation,” facilitating processes that do.20 Frischmann, supra note 17, at 4; Jeffrey E. Fulmer, What in the World is Infrastructure?, Infra. Investor, July-Aug. 2009, at 30, 32 https://30kwe1si3or29z2y020bgbet-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/what-in-the-world-is-infrastructure.pdf [https://perma.cc/TY9A-VWJD] (Defining infrastructure as “[t]he physical components of interrelated systems providing commodities and services essential to enable, sustain, or enhance societal living conditions”).

Because this Article largely focuses on economic infrastructure, and transportation specifically – with case study-specific elements denoted in Figure 121See infra Parts II, III (detailing MTA case study, as labeled).

– for the sake of relative simplicity, it will at times use the term ‘infrastructure’ to reference just those elements of the broader taxonomy.

2. An Imperfect Public Good with Externalities

Contemporary legal frameworks can (albeit, sometimes unintentionally) trend towards viewing public goods and private goods as a binary choice,22Jesse Malkin & Aaron Wildavsky, Why the Traditional Distinction Between Public and Private Goods Should Be Abandoned, 3 J. Theoretical Pol. 355 (1991); Elinor Ostrom, Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems, 100 Am. Econ. Rev. 641 (2010).

roughly corresponding to the respective public and private law frameworks.23This is not always the case, of course. Commercial law involves both public and private law; bankruptcy, for instance, is a federal statutory framework for addressing bilateral (private) economic relationships. The interplay in commercial law, however, is distinct from this discussion, which is perhaps more akin to blending across the spheres rather than coordination amongst silos.

Accordingly, infrastructure is frequently termed a “public good,”24Professor Garrett, former Dean of Wharton, noted that “[t]he classical position on infrastructure is that it is a ‘public good’— something critical to society that ‘the market’ would undersupply — and hence the natural domain of government.” Geoffrey Garrett, What the U.S. Could Learn from Australia About Financing Infrastructure, Knowledge at Wharton (June 8, 2018), https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/u-s-needs-embrace-private-sector-involvement-infrastructure/ [https://perma.cc/2CEB-BH6L].

the traditional economic definition of which requires that it be:25See Paul A. Samuelson, The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure, 36 Rev. Econ. & Stat. 387, 387 (1954) (defining a “collective consumption good” as “[goods] which all enjoy in common in the sense that each individual’s consumption of such a good leads to no subtractions from any other individual’s consumption of that good . . . “); see also Richard Musgrave, The Theory of Public Finance: A Study in Public Economy (1959) (incorporating non-excludability criterion); Hal R. Varian, Microeconomic Analysis (W.W. Norton & Co. 3d ed. 1992) (conceptualizing “public goods” as meeting both Samuelson’s non-rivalrous standard and Musgrave’s non-excludability criterion).

(1) ‘non-rivalrous’26“Non-rivalrous” can be broadly defined as accessible by all such that one individual’s use does not impede another’s. Perhaps the simplest example of a rivalrous good is food; once consumed, it is no longer accessible to others.

and (2) ‘non-excludable.’27“Non-Excludable” can be defined as being such that it is impossible to prevent other individuals from consuming it. See supra note 16. For further discussion, see Breydo, supra note 8, at 1045.

Yet, in reality, infrastructure28This contextualization is intended to be with respect to economic infrastructure, and particularly transit. There are of course important applicable asset-type-specific distinctions. See infra Part IV.A.

is closest to an imperfect (or impure) public good: one that satisfies the two conditions only to a certain extent, or only some of the time.29Aman A. Bara & Bidisha Chakraborty, Is Public-Private Partnership an Optimal Mode of Provision of Infrastructure?, 44 J. Econ. Dev. 97, 97, 99 (2019) (“This paper considers infrastructure as an impure public good and examines whether a public-private partnership in financing infrastructure service is optimal,” finding “that PPP model is optimal in the provision of infrastructure no matter public capital and private capital are a substitute or complementary to each other.”).

For instance, a lighthouse or road without tolls or traffic can functionally resemble a public good. Yet, that same road can also feel closer to a private good through the rivalrous impact of rush-hour traffic and exclusionary effect of tolls. The imperfect public good construct informs much of the incongruence, and, at times, inconsistency, in how society and policy makers view infrastructure.30Randall Bartlett, Is Infrastructure a Public Good? No, Sort of, and What Role for the Public and Private Sectors, Inst. Fiscal Stud. & Democracy (May 15, 2017), https://www.ifsd.ca/en/blog/last-page-blog/infrastructure-public-good [https://perma.cc/WTB2-ETPA].

Conceptualizing infrastructure as an imperfect – rather than ‘pure’ – public good supports deep government involvement but does not create a normative disconnect in respect of private sector participation or multi-stakeholder models.

Infrastructure also exhibits “externalities,” defined as second order effects on individuals not party to a transaction.31R. H. Coase, The Problem of Social Cost, 3 J. L. & Econ. 1 (1960).

Specifically, infrastructure can generate positive externalities through increased efficiency and other economic effects, and, critically for our purposes, reduce negative externalities. For instance, driving produces negative externalities through pollution, noise and congestion – indeed, the transportation sector accounts for 36% of U.S. emissions.32Brett Marohl, Today in Energy, U.S. Energy Info. Admin. (July 26, 2021), https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=48856 [https://perma.cc/6PRB-GGMP].

Public transit – with some of the lowest carbon emissions per kilometer traveled – can provide an externality-minimizing substitute, essential for emissions goals, thus enhancing the aggregate welfare.33Which form of Transport Has the Smallest Carbon Footprint?, Our World in Data (Aug. 30, 2023), https://ourworldindata.org/travel-carbon-footprint [https://perma.cc/7AMG-VT45].

3. Market Disequilibrium

Infrastructure is essential for both economic activity and quality of life. Yet, the ‘market’ for it exhibits pervasive disequilibria.

Economists have attributed America’s brisk post-World War II growth in part to robust infrastructure investment.34David Alan Ashauer, Why is Infrastructure Important?, in Conference Series (Federal Reserve Bank of Boston) 21, 21-68 (1990).

A large-scale ‘meta study’ of 3,000 papers found an average cumulative ‘multiplier effect’ of one-point-five times,35Fiscal Multiplier Effect of Infrastructure Investment, Global Infrastructure Hub (Dec. 14, 2020), https://www.gihub.org/infrastructure-monitor/insights/fiscal-multiplier-effect-of-infrastructure-investment/ [https://perma.cc/Y5Z4-ZC5G] (finding an average 2-5 year cumulative multiplier of 1.5x, and 1.6x in recessionary environments, compared to 1.0x and 1.4x for public spending as a whole).

while other research indicates a three-times multiplier for transportation investment.36 Jeffrey Werling & Ronald Horst, Nat’l Ass’n of Manufacturers Catching Up: Greater Focus Needed to Achieve a More Competitive Infrastructure 45 (2014), https://www.ourenergypolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Infrastructure-Full-Report-2014.pdf [https://perma.cc/2DME-GWPQ].

Other studies have found that traffic congestion costs the U.S. up to $120 billion per year, while airport delays add up to over $35 billion annually.37See McBride et al., supra note 2; Erik Hansen, To Fix America’s Infrastructure, Start with Airports, U.S. Travel Ass’n (May 19, 2017), https://www.ustravel.org/news/fix-america%E2%80%99s-infrastructure-start-airports.

Despite the well-understood importance of infrastructure, markets, both public and private, have a hard time providing a societally optimal supply of foundational shared resources. The aforementioned U.S. ‘infrastructure funding gap’ – estimated between $2.6 and $3.8 trillion – is, in essence, a market disequilibrium.38See Am. Soc’y of Civ. Eng’rs, supra note 3, at 8 (estimating .6 trillion investment gap); Investment Forecasts for United States, Glob. Infrastructure Hub: Infrastructure Outlook, https://outlook.gihub.org/countries/United%20States [https://perma.cc/HM8B-8F99] (estimating .8 trillion U.S. investment gap in 2021).

At present, U.S. infrastructure spending as a percentage of GDP is the second lowest amongst the G20, ahead of only Mexico, resulting in by far the largest investment gap amongst G7 nations.39See McBride et al., supra note 2.

Illustrating the real-world implications, on January 28, a Pittsburgh bridge collapsed shortly before a scheduled speech by President Biden regarding the 2021 IIJA.40Campbell Robertson & Sophie Kasakove, Pittsburgh Bridge Collapses Hours Before Biden Infrastructure Visit, N.Y. Times (Jan. 28, 2022). https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/28/us/pittsburgh-bridge-collapse-biden.html [https://perma.cc/8PQ2-4TEN].

Beyond the headlines, society experiences the consequences of this market breakdown daily through transit delays, gridlocked traffic and power outages.41See, e.g., Denchak, supra note 12 (discussing the Flint water crisis).

As the full costs of climate change are internalized, the importance of infrastructure will only grow – as will the costs of our prevailing disequilibrium, and the failure to act.42 Jonathan Woetzel et al., Will Infrastructure Bend or Break Under Climate Stress? 23 (2020), https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability/our-insights/will-infrastructure-bend-or-break-under-climate-stress [https://perma.cc/J6WE-Y5AR] (noting that infrastructure is essential to climate change mitigation and will “bear the brunt” of adaptation costs.); Mekala Krishnan et al., The Net-Zero Transition viii (2022), https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/sustainability/our-insights/the-net-zero-transition-what-it-would-cost-what-it-could-bring [https://perma.cc/X9GL-76J2] (estimating global annual cost of .2 trillion to achieve net-zero transition).

B. U.S. Approach: Public Sector-Centered Model

Though the U.S. often views itself as highly centered around free markets and private assets, it follows a markedly different approach with respect to most infrastructure. Relative to other jurisdictions, the U.S. generally places a heavier emphasis on public sector infrastructure ownership and financing.43There are notable asset-specific distinctions to this construct; specifically, water and transit are largely public sector-centric, while there is more capital in respect of the regulated utility sector.

At the same time, largely as a function of dual-federalism, the U.S. delegates this responsibility to the state and local levels, with infrastructure assets typically financed through a combination of taxes and municipal bonds.

1. Normative Underpinnings

The ‘public good’ normative construct appears to underpin much of the U.S. approach to infrastructure.44See supra Part I.A.2. Infrastructure presents a number of distinct and important dimensions, particularly in respect of frameworks regarding ownership and control. Some of the issues are previewed, infra Part IV, but comprehensively unpacking the normative layers remains an area of ongoing and future research.

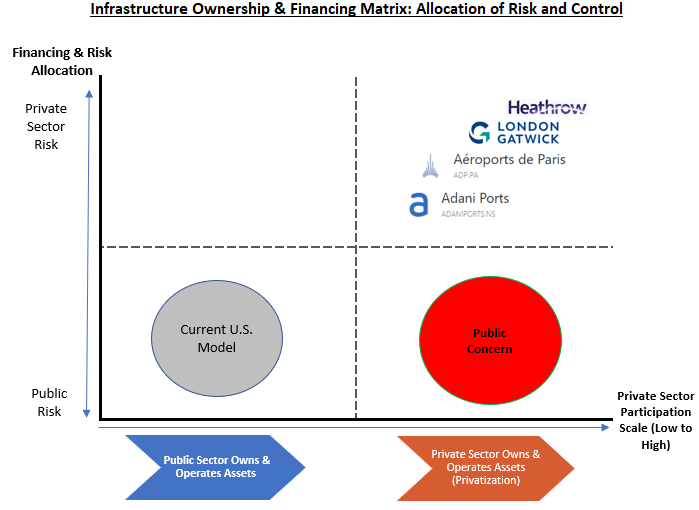

Figure 3 below charts infrastructure finance against the level of private sector participation, creating a two-by-two matrix. The U.S. model in the bottom left quadrant, maps to public sector financing and control.45Though often used interchangeably, ‘funding’ and ‘financing’ have distinct meanings in the infrastructure context. ‘Financing’ refers to the party providing capital and ‘owning’ risk; ‘funding’ refers to how infrastructure will be paid for. World Bank, Public-Private Partnerships Reference Guide 21 (3d ed. 2017), https://ppp.worldbank.org/public-private-partnership/sites/ppp.worldbank.org/files/documents/PPP%20Reference%20Guide%20Version%203.pdf [https://perma.cc/5ZXH-YJA8]; Richard Abadie, The Global Forces Shaping the Future of Infrastructure 13 (2021), https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/capital-projects-infrastructure/pdf/global-infrastructure-trends.pdf [https://perma.cc/5P2N-WYXN]. Consistent with the World Bank framework, and for purposes of relative simplicity, this model views “participation” as encompassing elements of both ownership and operational control. See infra note 87.

Figure 2. Matrix: Infrastructure Risk & Control Allocation

The top right quadrant maps to “privatization,” with certain private sector-owned infrastructure assets.46As discussed, for purposes of this Article, ‘privatization’ refers to the outright sale of assets, rather than hybrid models, such as public-private-partnerships. See supra Part I.C.

The bottom right quadrant reflects a common public perception regarding privatization: private gains, socialized costs.47In other words, perception of arrangements where “governments essentially guarantee . . . substantial payments” to investors, creating a “wealth transfer” at the expense of the public; see Matthew Goldstein & Patricia Cohen, DealBook, N.Y. Times (June 6, 2017), https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/06/business/dealbook/trump-infrastructure-plan-privatized-taxpayers.html; Damon A. Silvers, Private Infrastructure Projects Are a Wealth Transfer from the Public to Wall Street, N.Y. Times, (Apr. 8, 2015, 6:47 AM), https://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2015/04/08/does-the-public-benefit-from-private-infrastructure-investment/private-infrastructure-projects-are-a-wealth-transfer-from-the-public-to-wall-street [https://perma.cc/3QB4-MCUD].

The negative connotation around “privatization” is not undeserved; privatization often carries negative consequences. For instance, in 2008, Chicago ‘privatized’ certain parking assets, resulting in a significant loss to the city.48Kristin E. Schultz, Note, Public-Private Partnerships: Structuring the Revival of Fiscally Distressed Municipalities, 15 N.Y.U. J.L. & Bus. 189, 207–09 (2018) (describing Chicago transaction as “exploitation”).

Privately-run prisons have been exceptionally problematic; the Justice Department found them “more violent” than government-run institutions and recommended a “phase out.”49Timothy Williams, Inside a Private Prison: Blood, Suicide and Poorly Paid Guards, N.Y. Times (Apr. 3, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/03/us/mississippi-private-prison-abuse.html [https://perma.cc/8NGN-L2X5].

However, the potential harms of ‘privatization’ – while quite real and significant – need not be inherent to private sector participation. Indeed, when coupled with comprehensive oversight, certain shared resources, such as telecommunications and electricity, can be ably provided by private operators.

2. Historical Context

Infrastructure ownership and financing structures in the U.S. have gone through multiple phases – briefly public, then private, and, for the last century, public again – underscoring that our contemporary conceptualization is not the only approach.

The history of U.S. infrastructure development displays something of a dissonance, underscored by “[t]wo sets of broad and at times conflicting ideas”50Charles Jacobsen & Joel Tarr, Ownership and Financing of Infrastructure: Historical Perspective (English) 4 (World Bank Grp., Working Paper No. 1466, 1995), http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/624581468765619582/Ownership-and-financing-of-infrastructure-historical-perspective [https://perma.cc/8YTL-CY4K] [hereinafter Infrastructure: Historical Perspective].

– an emphasis on maximizing “overall economic development and individual economic opportunity,”51Id.

tempered by “broad fears of irresponsible accumulations of either political or economic power.” 52Id.; Charles W. Calomiris & Stephen H. Haber, Fragile By Design: The Political Origins of Banking Crises and Scarce Credit, 153–202 (2014) (discussing historical U.S. concerns about concentrations of power as a reason for relative industry and regulatory fragmentation in the U.S. banking sector).

In simplified terms53This framework does not (or intend to) capture the complex history of U.S. infrastructure or public finance but merely seeks to illustrate that the prevailing frameworks have changed over time.

, U.S. infrastructure finance – particularly for transportation and public transit – has gone through essentially three phases.54Infrastructure: Historical Perspective, supra note 50, at 8-10.

The first, in the front half of the nineteenth century, saw extensive public sector investment in infrastructure assets.55 Robert W. Poole, Jr., Asset Recycling to Rebuild America’s Infrastructure 14 (Nov. 2018), https://reason.org/wp-content/uploads/asset-recycling-rebuild-america-infrastructure.pdf [https://perma.cc/342N-RL5L].

Subsequently, depressions in 1837 and 1857 were followed by a sharp contraction in public sector capital deployment due to resource limitations.56Id.

The second phase, from the mid-nineteenth century until around the Depression era, was marked by significant private investment.57 Clifford Winston, Last Exit: Privatization and Deregulation of the U.S. Transportation System 2 (2010) (noting that “by 1860 at least 7,000 private U.S. corporations had formed to operate bridges, canals, ferries, railroads, and roads.”); U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., GAO-08-44, Highway Public Private Partnerships: More Rigorous Up-front Analysis Could Better Secure Potential Benefits and Protect the Public Interest 11–12 (2008), https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-08-44.pdf.

Over time, however, many of the enterprises found themselves in financial distress, oftentimes due to frictions with respect to rate-setting.

That pullback in private capital led to the third phase, in effect today, characterized by an emphasis on public authorities, rather than the private market, assuming responsibility for infrastructure, and particularly transit.58Jacobsen & Tarr, supra note 50, at 8-10.

The MTA nicely illustrates this arc of U.S. infrastructure history. The system began as two privately owned, competing lines. Subsequently, in 1932, New York City began operating a third line, which was buttressed by significant government funding and credit.59Ameena Walker, NYC Subway Cars Throughout History: from Steam-Powered Engines To Open-Gangway Design, Curbed (Sept. 20, 2017, 2:08 PM), https://ny.curbed.com/2017/9/20/16305388/nyc-subway-history-mta-train-cars [https://perma.cc/W6TE-QX8Z].

A dispute regarding fare increases followed. By 1940, NYC orchestrated a merger of the three entities. Following a transition period of relatively independent operation, the entities become more closely integrated, ultimately leading to the present-day structure.60See Part III.

The questions then were not dissimilar to those discussed today. In 1941, one scholar observed:

The administrative problems that appear where government becomes an entrepreneur and manager had indeed been present since 1932 . . . But unification raises in full force difficult questions in the adaptation of governmental concepts and procedures to the conduct of economic undertakings.61Arthur W. Macmahon, The New York City Transit System: Public Ownership, Civil Service, and Collective Bargaining, 56 Pol. Sci. Q. 161, 161 (1941) (emphasis added).

3. Federalism & Municipal Finance

Along with a public sector emphasis, a second distinctive dimension of U.S. infrastructure finance is the delegation of responsibility to the state and local levels, rather than the federal government.

This delegation reflects America’s dual-federalist framework, a constitutional construct where individual states are themselves sovereign, with powers not granted to the federal government generally reserved for the state level.62The construct is not entirely unique to the U.S. but is perhaps more pronounced. In many other nations, sub-national units of government are functionally more akin to administrative entities, with the ability to issue their own debt but generally lacking the powers of a sovereign. See U.S. Const. amend. X (“The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people”); Steven L. Schwarcz, Global Decentralization and the Subnational Debt Problem, 51 Duke L.J. 1179, 1179-250 (2002). As a consequence of dual-sovereignly, U.S. states are ineligible for bankruptcy, while municipal entities in respective states must be specifically authorized to utilize Chapter 9. See supra Part II.B.

As part of this division of labor, the states are traditionally responsible for providing – and financing – a range of economic63 U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., supra note 57, at 12 (2008) (noting state responsibility to maintain highways).

and non-economic infrastructure, including police, education and healthcare.64Charles M. Tiebout, A Pure Theory of Local Expenditures, 64 J. Pol. Econ. 416, 418 (1956) (observing “Musgrave and Samuelson implicitly assume that expenditures are handled at the central government level. However, the provision of such governmental services as police and fire protection, education, hospitals, and courts does not necessarily involve federal activity. Many of these goods are provided by local governments”).

At the same time, the states retain control over land use and property laws, both of which are critical for physical asset development.65See, e.g., Joseph F. Zimmerman, National-State Relations: Cooperative Federalism in the Twentieth Century, 31 Publius 15 (2001); James R. Alexander, State Sovereignty in the Federal System: Constitutional Protections Under the Tenth and Eleventh Amendments, 16 Publius. 1(1986).

Within the states, allocation of power is further sub-divided at various levels, with public corporations often used as financing vehicles for infrastructure and other capital spending.66A significant amount of U.S. infrastructure is formally owned at the county level, including 38% of bridges. Legislative Analysis for Counties: The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, National Association of Counties (Mar. 4, 2022), https://www.naco.org/resources/legislative-analysis-counties-bipartisan-infrastructure-law.

As a consequence, the U.S., in effect, has two relatively distinct ‘sovereign’ debt markets – the $21 trillion treasuries market, which reflects federal borrowing, and the $4 trillion municipal bond market, which reflects state and municipal entities.67The much larger U.S. Treasury market is used to fund the federal government, which may at times downstream resources to support the states, including through Covid-19 relief programs. See infra Part II.A.3.c.

About two-thirds of infrastructure projects are funded through municipal bonds issued by state and local governments; infrastructure, in turn, represents the bulk of municipal debt.68 Muni. Sec. Rulemaking Bd., Muni Facts 1 (2020), http://iabcn.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/MSRB-fact-sheet.pdf.

The municipal market is composed of two main instruments: (1) “full faith and credit” general obligation bonds and (2) revenue bonds, used to finance infrastructure like the MTA.69 . Sec. & Exch. Off. of Inv. Educ. & Advoc., Municipal Bonds: Understanding Credit Risk 1, https://www.sec.gov/files/municipalbondsbulletin.pdf. See infra Part II.A.2 (detailing the MTA’s revenue bond-financed capital structure).

Three features of revenue bonds are notable for our purposes.

First, the “revenue bond” structure exists because municipal entities generally cannot borrow on a ‘traditional’ secured basis,70 Juliet M. Moringiello, Municipal Capital Structure and Chapter 9 Creditor Priorities 5 (2016), https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/moringiello1.pdf [https://perma.cc/SKX3-KXFG] (“Creditors of private entities have recourse to the entity’s property in the event of non-payment. Creditors of public entities do not because the law considers municipal property to be held in trust for the public. Access to property is a key feature in the design of creditors’ rights laws, but municipal creditors have no rights to their debtors’ assets”).

due to difficulties of lien enforcement with respect to government property.71The basic issue is that action against governmental property can raise police power-related concerns. See David A. Skeel, Jr., What Is a Lien? Lessons from Municipal Bankruptcy, 2015 U. Ill. L. Rev. 675, 697 (2015); Moringiello, supra note 70 at 9, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/moringiello1.pdf [https://perma.cc/SKX3-KXFG] (“By statute, custom, and common law, municipalities are restricted in their ability to grant security interests in other property” beyond the dedicated revenue stream, which “prohibit[s] creditors from seizing municipal assets to satisfy claims against the municipality”).

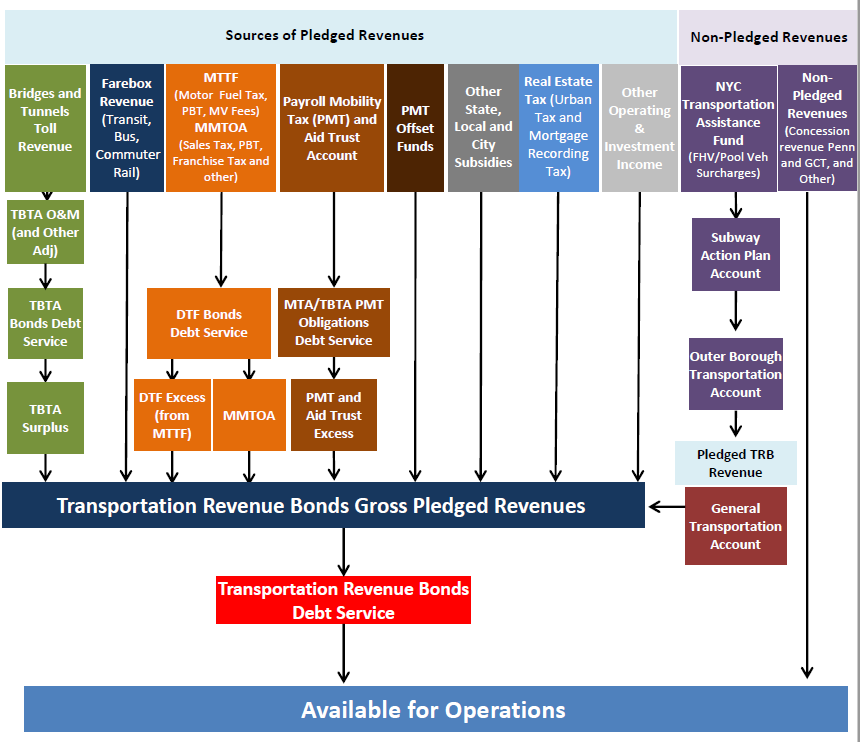

Revenue bonds bypass this challenge by granting liens in a circumscribed revenue stream – typically infrastructure, but also dedicated taxes72Lev Breydo & Sean O’Neal, Will the USVI Follow Puerto Rico’s Path?, Bond Buyer (Mar. 27, 2017, 11:17 AM), https://www.bondbuyer.com/opinion/will-the-usvi-follow-puerto-ricos-path (discussing the USVI’s tax-backed revenue bond structure). See supra Part II.A.2, discussing MTA capitalization.

— which forms the co-called “Trust Estate,” rather than in the revenue-producing asset.73Through revenue bonds, a lender receives security in the form of a pledge of revenues – though, special revenue bonds are non-recourse debt, making the bonds payable only from the municipality’s pledged special revenues. In re Heffernan Mem’l Hosp. Dist., 202 B.R. 147 (B.A.P. 9th Cir.1996).

Revenue bonds’ cash flow function is essentially a waterfall. For instance, with respect to an infrastructure project, gross revenues from user fees might first be used to cover operating expenses, with remaining net revenue flowing to the trust estate, and then to bondholders, with any excess funds kept in reserve or used for other debt needs.74Security for special revenue bonds can be in the form of: (i) A gross pledge where the bondholders’ lien attaches to the entire revenue stream; or (ii) A net pledge, where the bondholders’ lien attaches only to the revenues that are in excess of the expense of the operation and collection. Bank of N.Y. Mellon v. Jefferson Cty. (In re Jefferson Cty.), 482 B.R. 404, 434-35 (Bankr. N.D. Ala. 2012).

Second, revenue bonds can receive special statutory protections in bankruptcy, with well-documented legal difficulties in ‘impairing,’ or reducing, such obligations, complicating infrastructure financial distress.75Special revenue bonds receive unique protections under section 922 of the bankruptcy code, and until recently those protections were understood to include collection of post-petition interest. Id. at 428-27; see also David A. Skeel Jr., Is Bankruptcy the Answer for Troubled Cities and States?, 50 Hous. L. Rev. 1063 (2013); Alexander D. Flachsbart, Municipal Bonds in Bankruptcy: §902(2) and the Proper Scope of “Special Revenues” in Chapter 9, 72 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 955, 982 (2015) (“The first key to bondholder treatment in municipal bankruptcy is the presence or absence of property rights to municipal revenue.”).

For natural monopolies, the challenge is particularly pronounced, as it can effectively require rate increases beyond what their constituencies can afford.76For instance, some courts have required issuers to raise rates in order to repay bond obligations. See State ex rel. Allstate Insurance Co. v. Union Public Service District, 151 S.E.2d 102 (W. Va. 1966); see also Robert S. Amdurskyet al., Municipal Debt Finance Law: Theory and Practice, 336-40 (2d ed. 2013) (“The remedy as interpreted in Allstate effectively shifts the risk of the project’s success from bondholders to the ratepayers.”). More recently, some of the most difficult issues with the Puerto Rico restructuring arose in respect of the Commonwealth’s utilities.

Though recent decisions have pared back certain revenue bond protections, significant uncertainty remains.77In a 2019 decision the First Circuit held that the holders of special revenue bonds cannot compel the debtor to apply special revenues to debt service postpetition (though the debtor could do so voluntarily). In re Fin. Oversight & Mgmt. Bd. for Puerto Rico, 919 F.3d 121, 132 (1st Cir. 2019). See Laura E. Appleby et al., First Circuit Panel Upends Protections Available to Special Revenue Bondholders, 15 Pratt’s J. Bankr. L. 1, 1(2019).

This broad-based set of legal issues illustrates the fact that, while certain aspects of the MTA’s restructuring challenges described in Part II are distinctive, they are, fundamentally, manifestations of wider concerns regarding resolution of infrastructure financial distress – and requiring broad-based solutions.

Finally, municipal bonds are typically tax-exempt for residents of the issuing state, which encourages individuals to hold municipal bonds directly,78Unlike corporate debt, most municipal bonds are held by individuals – 46% directly, and 26.8% through mutual funds (per SIFMA data) — on a geographically circumscribed basis.

but can disincentivize investment by already-tax-exempt institutional investors, such as pension funds.79A GAO Report found that “pension plans have no incentive to invest in lower-interest municipal bonds, since plan earnings are already tax exempt.” U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., GAO-95-173, Private Pension Plans: Efforts to Encourage Infrastructure Investment 3 (1995), https://www.gao.gov/assets/hehs-95-173.pdf. This is notable because the premise of leveraging pension asserts to fund infrastructure investment is commonly suggested. See Clive Lipshitz & Ingo Walter, Bridging Public Pension Funds and Infrastructure Investing 42 (2019); Caitlin Devitt, Infrastructure Bill Features First-of-Its-Kind P3 Asset Recycling Requirement, Bond Buyer (Nov. 9, 2021, 1:57 PM), https://www.bondbuyer.com/news/infrastructure-bill-may-boost-asset-recycling (“If government-owned assets come into play [through the IIJA], U.S. public pension funds make natural investors.”).

C. Global Perspective: Public-Private ‘Hybrid’ Models

Over time, many jurisdictions around the world have become more receptive to private sector participation in infrastructure, resulting in what this Article terms ‘hybrid’ models.80See McBride et al., supra note 2.

For purposes of discussion, at a simplified level, the approaches can be segmented between three main categories:

● United States. Heavy emphasis on public sector infrastructure ownership and finance.81This is particularly with respect to transportation and water infrastructure; energy and telecommunications infrastructure have incorporated more private capital, as well as somewhat distinct business models. See id. (“United States invests less in transportation infrastructure as a percentage of GDP than many other wealthy countries, including France, Germany, Japan and the United Kingdom.”).

● Europe. Generally favoring hybrid models, including Public-Private Partnerships.82Ronald W. McQuaid & Walter Scherrer, Public Private Partnership in the European Union: Experiences in the UK, Germany and Austria, 6 Cent. Eur. Pub. Admin. Rev. 7, 7 (2008) (“The political context of governments differs between the UK, Germany and Austria, but each government currently has a positive view of Public private Partnership (PPP). There are many similarities to the drivers for PPPs in Austria, Germany and the UK.”); Yong Hee Kong, European Experiences in PPP (and some regional countries), Address at the Public Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility’s Session on Private Sector Participation (2007) (noting that in 2004/5, more than 150 PPP transactions closed in Europe “more than ½ of world total”).

● Japan and Australia. Higher prevalence of privately-owned infrastructure assets. 83William Langley, Sydney Airport Agrees .5bn Takeover Deal with Pension Funds, Fin. Times (Nov. 8, 2021), https://www.ft.com/content/00ecc8a7-7f94-444e-bd8b-5e5d516ceec9. In 1987, Japan privatized Japan Railways Group, dividing it into seven for-profit stock companies, four of which are publicly-listed. Eleanor Warnock, Lessons from Railway Privatization in Japan, Tokyo Rev. (Oct. 11, 2018), https://www.tokyoreview.net/2018/10/japan-railway-privatization; see also Stephen Smith, Why Tokyo’s Privately Owned Rail Systems Work So Well, Bloomberg (Oct. 31, 2011, 7:15 AM), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2011-10-31/why-tokyo-s-privately-owned-rail-systems-work-so-well; Max Zimmerman, What The World Can Learn From Life Under Tokyo’s Rail Tracks, Bloomberg (Sept. 10, 2020, 5:00 PM), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2020-09-10/what-the-world-can-learn-from-life-under-tokyo-s-rail-tracks; John Calimente, Rail Integrated Communities in Tokyo, 5 J. Transit & Land Use 19, 19 (2012).

This sub-section presents an intellectual framework underlying the ‘hybrid’ model, and details specific approaches and considerations with respect to public-private-partnerships, and particularly concessions.84See infra Part III.

Then, it outlines asset recycling, which underlies the proposal in Part III, and discusses certain disappointing dimensions of the 2021 Infrastructure Act.

1. ‘Hybrid’ Models Overview

‘Hybrid’ models incorporating public and private sector capital and participation are not new and have long existed in varying forms across different sectors, in the U.S. and abroad.85See Jody Freeman, The Contracting State, 28 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 155, 166 (2000).

Conceptually, the ‘hybrid’ approach is perhaps closer aligned with the imperfect public good construct.86See supra Part I.A.2.

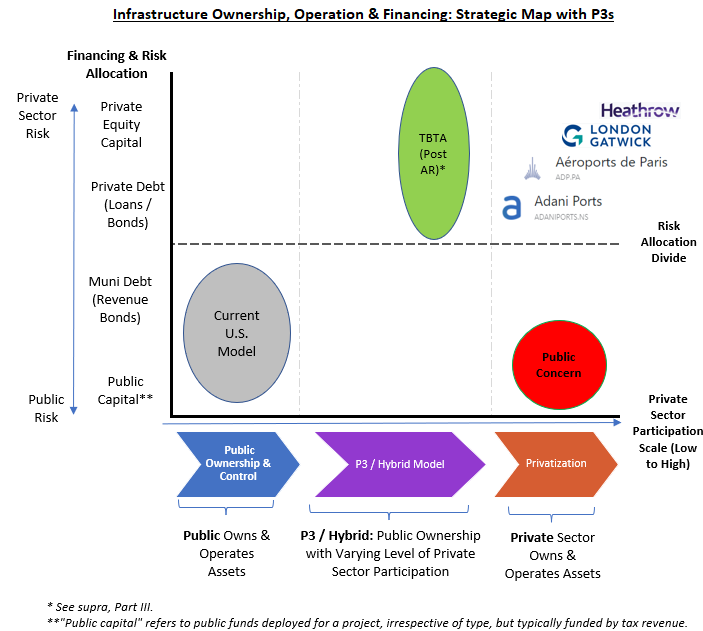

Figure 4 below visualizes this by building on an existing World Bank framework – which provides the horizontal axis, detailing a continuum of hybrid approaches – to incorporate the vertical axis of financing options with differing levels of private sector risk assumption.87PPP Arrangements/Types of PPP Agreements, World Bank, https://ppp.worldbank.org/public-private-partnership/agreements (last visited Oct. 24, 2024).

The critical insight is the large area in the middle – corresponding to four common types of ‘hybrid’ structures (detailed below) utilized in other jurisdictions – which illustrates vast latent optionality:

Figure 3. Strategic Map: Infrastructure Ownership, Control & Financing

As before, the U.S. model maps to the bottom left portion, with government ownership and financing; the top right box reflects a structure closest to full privatization. The level of private sector participation increases as one moves from left to right along the x axis.

Conceptually, it is logical that for a particular asset, or asset types, the optimal ownership and capitalization structure can differ, and also evolve over time. In that respect, the division of labor and responsibility between public and private arguably has some parallels to (as well as critical distinctions from), the separation of ownership and control well-documented in the corporate context.88See infra Part IV.

2. Public-Private Partnerships: Concessions

Of the four ‘hybrid’ structures, leases and concessions generally map closest to the prevailing American conception of ‘public-private partnerships,’ or ‘P3.’89See Kelsey Hogan, Note, Protecting the Public in Public-Private Partnerships: Strategies for Ensuring Adaptability in Concession Contracts, 2014 Colum. Bus. L. Rev. 420, 422 (2014) (describing P3s).

Though terminology can vary, for our purposes, we can think of the definition of ‘public-private partnership’ as a “legally binding contract between a public sector entity and a private company . . . where the partners agree to share some portion of the risks and rewards inherent in an infrastructure project.” 90See Patrick Sabol & Robert Puentes, Private Capital, Public Good: Drivers of Successful Infrastructure Public-Private Partnerships, 4 (2014), https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/BMPP_PrivateCapitalPublicGood.pdf [https://perma.cc/62QS-HWTT] (providing above P3 definition, while noting “elusive” nature of “precise” definition); see also U.S. Dep’t of Transp., Report to Congress on Public-Private Partnerships viii (2004) (defining a P3 as a “contractual agreement formed between public and private sector partners, which allows more private sector participation than is traditional’); Marta Marsilio et al., The Intellectual Structure of Research into PPPs, 13 Pub. Mgmt. Rev. 763, 764 (2011) (“Although…there is still no consensus regarding its definition, considerable research into PPPs has been published…”).

Concessions, a type of P3 (and, in turn, a subset of ‘hybrid’ models) are the primary focus of discussion, as they underlie the proposal discussed in Part III with respect to the MTA.91See infra Part III.

The general concession transaction structure entails a private entity assuming the operation of a project, which is then typically funded through a usage-based model.92There is a well-established precedent upholding these types of agreements, particularly in respect of natural monopoly assets. See The Binghamton Bridge, 70 U.S. (3 Wall.) 51, 74 (1865) (holding “if you will embark, with your time, money, and skill, in an enterprise which will accommodate the public necessities, we will grant to you, for a limited time period or in perpetuity, privileges that will justify the expenditure of your money, and the employment of your time and skill.”).

Through the transaction, the public entity:

● Receives an up-front payment;93The monetization process typically involves a large-scale marketing effort, with the concession price set at auction. See supra Part I.C (discussing the Indiana Toll Road).

● Retains title and legal ownership of the asset;94The private sector entity is, formally, a newly-created special purpose vehicle, capitalized with debt and equity from investors. Investors own that vehicle, not the infrastructure asset itself.

● May retain some economics, based on the structure;95For instance, the government of NSW retained significant economics in certain assets. See infra note 118.

● No longer bears responsibility for operating and maintenance expenses (or demand risk) 96See Emily Thornton, Roads to Riches, Bloomberg, (May 7, 2007, 12:00 AM), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2007-05-06/roads-to-riches [https://perma.cc/CJY2-6WFN] (“The burden of maintaining roads, bridges, and other facilities . . . is becoming difficult to bear. Federal, state, and local governments need to spend an estimated 5.5 billion improving highways and bridges in 2007…up 50% over the past 10 years.”).

; and

● Maintains comprehensive regulatory oversight and governance.97See infra note 117-20 and accompanying text.

Concessions are distinct from ‘sales,’ as the government retains title and ownership, while allowing for significant contractual tailoring and economic oversight, well beyond what would be realistically feasible following a sale.98See infra Part III.C. (discussing distinctions).

Fundamentally, concessions and P3s are about optimizing the allocation of the portfolio of risks associated with an infrastructure project.99See Martin Blaiklock, Infrastructure Finance: An Inside View (2017).

Traditionally, in the U.S., those risks have been warehoused solely within the public sector. Reasoning from finance first principles, however, suggests that specific risks should be allocated to the particular parties best suited to bear them. For infrastructure, that re-allocation is core to P3 value creation.100“PPPs that do not transfer risk—and benefit from the private-sector’s risk-management capabilities—will likely fall short of expectations.” Frank Beckers & Uwe Stegemann, A Smarter Way to Think About Public-Private Partnerships 2 (Sept. 10, 2021), https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/risk-and-resilience/our-insights/a-smarter-way-to-think-about-public-private-partnerships.

Relative to the public sector, the private sector is typically better equipped to handle certain exposure, such as demand forecasting, financing structures and construction management, 101The private sector is, broadly speaking, generally best equipped in handling tasks more closely resembling typical private entity endeavors, often involving an element of risk management and resource allocation. Id. at 3-4. Beckers and Stegemann add:

In the private sector…construction and commercial risks can have massive financial consequences…For this reason, successful private contractors have built up strong capabilities in risk management across the entire life cycle of a project, from development through construction to the end of the operating phase. And private investors and lenders have developed sophisticated controlling mechanisms—the “muscles” that companies cannot survive without.

Id. See also Matt Wheeler, Collaborative Project Investigates Public-Private Partnerships, Syracuse News (Apr. 26, 2017), https://news.syr.edu/blog/2017/04/26/collaborative-project-investigates-public-private-partnerships, writing:

[A study] found that public-private partnerships infrastructure projects in the United States have a significantly greater likelihood of meeting schedule and cost requirements when compared to conventional approaches…“These partnerships are not ideal for all projects, but they are a good option for big projects”…“We found that they are particularly well-suited for transportation, hospitals, schools and water systems.”

but generally ill-suited for others, particularly with respect to harnessing positive externalities,102 . The presence of broad-based externalities suggests that the private sector will tend to under-supply infrastructure (as it is agnostic towards externalities that it cannot capture). Are Big Infrastructure Projects Castles in the Air or Bridges to Nowhere?, The Economist (Jan. 16, 2017), https://www.economist.com/buttonwoods-notebook/2017/01/16/are-big-infrastructure-projects-castles-in-the-air-or-bridges-to-nowhere [https://perma.cc/F5EY-NGPH] (“Infrastructure can have positive externalities that are not captured by investors but will benefit society (the building of the internet or America’s interstate highway system, for example).”).

addressing legal uncertainty or working through regulatory and jurisdictional frictions.103Certain such considerations identified in a Federal Highway Administration study include regulatory risks, site risks, and permitting risks. See Fed. Highway Admin., U.S. Dep’t of Transp., Risk Assessment for Public-Private Partnerships: A Primer pt. 3, at 1-3 (2012), https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/pdfs/p3/p3_risk_assessment_primer_122612.PDF. A separate FHA analysis suggests that certain political risks, such as policy changes with impact on project economics “cannot be managed by the private party at all and would be expensively priced if transferred,” which suggests optimization through retention by the public entity. See Fed. Highway Admin., U.S. Dep’t of Transp., Guidebook for Risk Assessment in Public-Private Partnerships 33 (2013), https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/pdfs/p3/p3_guidebook_risk_assessment_030314.pdf.

Because of this, the typical role for the private sector has been ‘greenfield,’ or new-build infrastructure.104For ‘greenfield’ (i.e., new-build) projects, at a high level, the process can be broken down into five phases: (i) design; (ii) building; (iii) finance; (iv) maintenance; and (v) operation. Fed. Highway Admin., U.S. Dep’t of Transp., supra note 103, at 1-1; see also Public-Private Partnership Model and its Merits in Attracting Foreign Direct Investment, Mahanakorn Partners Grp. (June 22, 2017), https://mahanakornpartners.com/public-private-partnership-model-and-its-merits-in-attracting-foreign-direct-investment.

The other core infrastructure project categories – ‘brownfield,’ referencing existing operating assets, or ‘rehabilitation,’ an intermediate category – are generally seen as preserve of the public sector, inapposite for private entities.105See E. R. Yescombe & Edward Farquharson, Public-Private Partnerships for Infrastructure—Principles of Policy and Finance 40-47 (2nd ed. 2018) (hereinafter “P3s for Infrastructure”); Practical Law Finance, Public Private Partnerships: Issues and Considerations, https://us.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/3-504-9995 (last visited Feb. 12, 2022); Barbara Weber et al., Infrastructure as an Asset Class: Investment Strategy, Sustainability, Project Finance and PPP 19-22 (2nd ed. 2016) (hereinafter “Infrastructure as an Asset Class”).

Some scholars explicitly consider P3s inapplicable to brownfield projects.106“Private-sector acquisition or management of existing public infrastructure without any major new capital investment or upgrading is not considered to be a PPP as defined here.” P3s for Infrastructure, supra note 105, at 9.

3. Asset Recycling

The traditional conception of P3s as only applicable to ‘greenfield’ projects historically rendered the decision framework for brownfield assets rather binary: (i) continued public sector ownership or (ii) full privatization.107‘Privatization’ is defined as the outright sale of an asset, including transfer of title, thus distinct from the proposals discussed herein.

More recently, Australia pioneered a third approach: asset recycling.108Gillian Tan, Wall Street Sees Big Wish Granted in Biden’s Infrastructure Deal, Bloomberg (June 24, 2021, 5:45 PM), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-06-24/wall-street-sees-big-wish-granted-in-biden-s-infrastructure-deal [https://perma.cc/N69B-WJME].

Asset recycling, or “A/R,” is a term of art for the two-phase process of (i) transitioning developed, mature infrastructure assets to private investors through a P3; and (ii) re-investing the proceeds in new infrastructure. The transaction is debt-neutral for the government, and intended to create a virtuous cycle with the asset developed in the second phase subsequently also recycled.109Geoffrey Garrett, Why the U.S. Needs to Embrace Private Sector Involvement in Infrastructure, Wharton Mag. (June 21, 2018), https://magazine.wharton.upenn.edu/digital/why-the-u-s-needs-to-embrace-private-sector-involvement-in-infrastructure/ [https://perma.cc/6EKP-FSZM] (advocating for Australia-pioneered asset recycling to close U.S. and global investment gaps); Richard Samans et al., Recycling Our Infrastructure for Future Generations 40 (2017).

The value creation could be vast. Professor Geoffrey Garrett, former dean of the Wharton School, estimates a potential asset recycling market size of $1.1 trillion, consistent with work by other researchers.110Garrett, supra note 109; see also Poole, Jr., supra note 55, at 6 (quoting an approximately trillion estimate for A/R market); Jigar Shah, It’s Time to Revitalise US Infra Through Asset Recycling, Infra Investor (May 6, 2020), https://www.infrastructureinvestor.com/its-time-to-revitalise-us-infra-through-asset-recycling.

As discussed in Part III, asset recycling can conservatively generate $33 to $53 billion in proceeds from a P3 concession for just the MTA’s bridge and tunnel assets.111As discussed and detailed, supra Part III and the figures are subject to model assumptions.

a. Two-Phase Process

As Australia’s former treasurer Joe Hockey explained, asset recycling developed as a function of necessity, finding it to be an effective way of enhancing productivity without straining government coffers. 112Joe Hockey, Asset Recycling in America (Nov. 27, 2018), https://web.archive.org/web/20190311130914/https://usa.embassy.gov.au/asset-recycling-america; see also Interview with The Hon Joe Hockey on Asset Recycling, The Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility– Global Infrastructure Hub (Mar. 24, 2023), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1TJVI42FXX8.

A nation’s infrastructure base can be conceptualized as two components: (i) the stock of brownfield or rehabilitation projects, with associated maintenance and operating expenses; and (ii) a flow of new greenfield assets, needed to support a growing economy while adjusting to exogenous shifts like climate change, and requiring up-front capital investment.113See supra notes 104-105 and accompanying text.

The innovation of asset recycling is that it leverages the stock of assets to finance development of the flow, in the process also reducing carrying costs and ideally creating a virtuous cycle of continued reinvestment.114Is an Infrastructure Boom in the works?, Economist (Jan. 2, 2021), https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2021/01/02/is-an-infrastructure-boom-in-the-works (observing large amounts of capital raised for infrastructure investment).

Fundamentally, asset recycling is thus an extension of the P3 framework but applied to ‘brownfield’ or existing infrastructure assets. Mechanically, the two-phase asset recycling process operates as follows:

- Monetization. The government monetizes revenue-generating public assets through P3, such as a long-term lease or concession.115See Part III.B detailing concession structure.

- Reinvestment. Monetization proceeds are re-invested:

- Typically, in new assets to allow subsequent ‘recycling’; or

- Rehabilitation of existing infrastructure assets.116 Practical Law Finance supra note 105.

Subsequently, the ‘new’ assets can also be recycled, creating a virtuous cycle, on a debt-neutral basis, as new investment is financed through from monetization of assets rather than borrowing.

b. Examples: Australia, Indiana and Puerto Rico

The Australian Asset Recycling Initiative (“ARI”) – as well as certain limited early U.S. transactions – illustrate the model’s application and value proposition.117Governance has been a critical feature of the program’s success, including development of a new agency focused on asset recycling. See Infrastructure, New South Wales, https://www.infrastructure.nsw.gov.au/; Financing Greenfield Infrastructure Through the Sale of Brownfield Infrastructure, Glob. Infrastructure Hub (Nov. 1, 2021), https://www.gihub.org/emerging-funding-and-finance/case-studies/financing-greenfield-infrastructure-through-the-sale-of-brownfield-infrastructure; see also Marsh & McLennan Companies, Infrastructure Asset Recycling for Governments and Investors 6-11, (2018), https://www.marsh.com/content/dam/marsh/Documents/PDF/asia/en_asia/Infrastructure_Asset_Recycling_APRC.pdf (hereinafter “MMC A/R Report”).

Australia presents a particularly apt comparable because, like the U.S., it has a dual-federalist system, with states delegated significant powers. The ARI optimized around this through state-led project selection, coupled with a 15% federal incentive for states that monetized assets and began new projects within specific timelines.

The state of New South Wales (NSW) was most active in Australia’s program, generating over $25 billion in proceeds as of 2018.118MMC A/R Report, supra note 117, at 10.

NSW structured certain transactions with retained economics, for instance selling only 50.4% lease interests in Ausgrid, the nation’s largest electricity distribution network, and Endeavour Energy, an electric generation operation.119Id.at 8-10; see also supra note 115 and accompanying text.

In all cases, the public sector largely maintained the pre-transaction regulatory structure, ensuring robust oversight.120For instance, with respect to Ausgrid: “[t]he State will continue its roles as licensor and safety and reliability regulator of Ausgrid, while the Australian Energy Regulator will continue to determine network revenue.” Past Projects, NSW Treasury, https://www.treasury.nsw.gov.au/projects-initiatives/commercial-transactions/past-projects (June 4, 2023).

At the same time, while relatively less common, a number of U.S. transactions have successful employed hybrid models, including asset recycling and P3s.

In 2006, the State of Indiana sold a 75-year concession to operate the 156-mile Indiana East-West Toll Road.121Because the winning consortium ultimately filed for Ch. 11, the transaction was sometimes considered a failure. Though deeper discussion is beyond the scope of this article, it is worth noting that the state did not retain economics, allowing it to keep the full up-front payment and protecting taxpayers, while the allocating of demand and financing risk to the private sector were not conceptually unreasonable. See generally Robert Puentes & Patrick Sabol, The Indiana Toll Road: How Did a Good Deal Go Bad? Brookings (Oct. 9, 2014), https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-indiana-toll-road-how-did-a-good-deal-go-bad.

Reflecting commercial best practices, Indiana utilized a robust investment bank-led marketing and auction process, leading to a $3.8 billion valuation,122The winning bid was 26.2% higher than the second, priced at an estimated 60.2x EBITDA multiple, with an 80% LTV financed by .03 billion of bank loans. Xin Zhang, An Analysis of the Current Investment Trend in the U.S. Toll Road Sector (June 2008) (S.M. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology) (on file with the Institute Archives and Special Collections, Massachusetts Institute of Technology), https://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/45620/320453281-MIT.pdf.

and negotiated extensive contractual protections, ranging from rate setting to trash removal.123 Aaron M. Renn, The Lessons of Long-Term Privatizations: Why Chicago Got it Wrong and Indiana Got it Right 9 (2016), https://media4.manhattan-institute.org/sites/default/files/R-AR-0716.pdf.

Additionally, the state was disciplined in capital allocation, reinvesting the $3.8 billion proceeds into other transportation projects, allowing for a fully-funded 10-year transportation program.124Ken Belson, Toll Road Offers New Jersey a Fiscal Test Drive, N.Y. Times (Apr. 13, 2008), https://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/13/nyregion/13indiana.html.

More recently, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey collaborated with private parties to modernize the LaGuardia (“LGA)125Sakshi Sharma, LaGuardia Airport PPP, US, IJGlobal, https://ijglobal.com/articles/101027/laguardia-airport-ppp-us (June 30, 2016, 11:37 AM); Kalliope Gourntis, LaGuardia, the US’ Largest P3, Reaches Financial Close, Infrastructure Inv. (June 2, 2016), https://www.infrastructureinvestor.com/laguardia-the-us-largest-p3-reaches-financial-close.

and JFK airports through P3s.126In 2017, the Airport Advisory Panel recommended to then-Governor Cuomo that the Port Authority utilize a P3 to make the necessary updates to JFK airport. The contemplated transaction entailed about billion of private capital for updates to 4 of JFK’s terminals. Airport Advisory Panel, A Vision Plan for John F. Kennedy International Airport 37-38 (2017), https://www.anewjfk.com/wp-content/uploads/pdf/JFK-Vision-Plan.pdf; Redevelopment Projects, A New JFK, https://www.anewjfk.com/projects/ (last visited Nov. 1, 2024); Paul Berger, Coronavirus Delays JFK Airport’s Billion Makeover, Wall St. J. (Aug. 9, 2020, 11:00 AM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/coronavirus-delays-jfk-airports-15-billion-makeover-11596985225.

Indeed, airports are a common P3 vector with a number of transactions announced and ongoing in the U.S. and abroad.127Examples of airport P3s include the Denver Airport, Chicago Skyway, Puerto Rico Airport, and internationally, the Melbourne Airport, Sydney Airport, Heathrow Airport, London Gatwick Airport, and Amsterdam Airport Schiphol. Airport Advisory Panel, supra note 126, at 37-38.

The LGA P3 transaction involved development of a revamped Terminal B, as well as certain associated improvements, with a new entity, LaGuardia Gateway Partners, serving as the project sponsor. Through the transaction, LaGuardia Gateway Partners was responsible for designing, building, financing, operating, and maintaining the project, with a lease period through 2050. Financing for the deal closed in 2016,128Gourntis, supra note 125.

though construction completion was meaningfully delayed by Covid-19.

The preliminary verdict appears positive. LaGuardia’s newly revamped Terminal B received accolades including – in what the Wall Street Journal compared to “Arby’s winning a James Beard”129Ben Cohen, LaGuardia Airport Is No Longer the Worst. This Team Fixed It., Wall St. J. (Sep. 15, 2022, 5:30 AM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/laguardia-airport-renovation-lga-terminal-b-11663203700.

– UNESCO’s 2021 Prix Versailles award for “best new airport in the world.”130LaGuardia Airport Terminal B Wins UNESCO’s Prestigious 2021 Prix Versailles for Best New Airport in the World, The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (Dec. 22, 2021), https://www.panynj.gov/port-authority/en/press-room/press-release-archives/2021-press-releases/laguardia-airport-terminal-b-wins-unescos-prestigious-2021-prix-versailles-for-best-new-airport-in-the-world.html.

While LGA’s P3 experience may prove above-average – Puerto Rico’s recent electric transmission P3, for instance, appears less than award winning131The Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority, or PREPA, the Commonwealth’s integrated electric monopoly, announced a plan to transition to a P3 structure. PREPA has been mired in a long-running billion restructuring, where revenue bond issues featured heavily, and is transitioning to the P3 structure in large part to deleverage. The transaction is structured as a long-term concession, with the government retaining asset ownership. Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico, 2021 Fiscal Plan for the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority 65 (2021).

– the transformation of “what was once regarded as the nation’s worst airport into a world-class facility” illustrates the latent potential for America’s aging infrastructure.132The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, supra note 131.

D. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act Falls Short

Though commendable for recognizing America’s infrastructure and climate-related challenges, the 2021 Infrastructure Act falls short on a number of dimensions. Most consequentially, the IIJA is estimated to provide only 18.2 to 22.4% of the ‘investment gap.’133This is because while the IIJA has a ‘headline’ number of .2 trillion, only 0 billion of the total is ‘new’ spending, with the balance reflecting funds already earmarked. At the same time, some of the 0 billion is allocated to categories that are not reflected in the ASCE ‘funding gap’ estimate. A range is provided to reflect potential distinctions in category alignments. For detailed analysis, see Breydo, supra note 8, at 1085.

In contrast, Australia’s ARI effectively leveraged private capital, coupled with extensive oversight, to enhance program scale without straining government budgets or sacrificing broader stakeholder priorities. If the IIJA was structured similarly – a 15% incentive match coupled with asset recycling – the legislation’s allocated capital could be sufficient to close the funding gap entirely.134The ARI in effect generally required only 15% of project capital to be from the Australian federal government, with the balance provided by the province. Correspondingly, based on the IIJA providing an estimated 18.2 to 22.4% of the investment gap, the observation is that this capital could theoretically be leveraged in a similar manner to provide an aggregate level of capital equal to roughly the funding gap.

The IIJA acknowledges a theoretical role for private capital, but rather unambitiously stops at the research phase, asking the Secretary of Transportation to submit a report with proposals to “address [] impediments” to private capital deployment, including asset recycling.135See Infrastructure and Investments Act, Pub. L. No. 117-58, § 611, 135 Stat. 562 (2021); Devitt, supra note 79.

As a related matter, the ARI was more fiscally efficient, creating a debt-neutral solution for the states, supported by transparent incentive funding from the federal government.

Unlike the IRA, IIJA funding is relatively murky, leaning on the Highway Trust Fund to the point of rendering it insolvent, with a Congressional Budget Office analysis of the legislation estimating a $191.5 billion shortfall by 2031.136 Cong. Budget Off., Highway Trust Fund Baseline Projections July 2021 2 (2021), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-07/51300-2021-07-highwaytrustfund.pdf (estimating 0 billion and .45 billion shortfalls in the highway and transit accounts, respectively).

That is important because, notwithstanding the generally positive multiplier associated with infrastructure investment, the net economic impact is highly sensitive to the funding profile, with the potential for negative economic returns from inapposite policy.137The Penn Wharton Budget Project found that the aggregate economic impact of the 2021 Infrastructure Act may be negative if it were entirely deficit financed, in large part due to the ‘crowding out’ effect of public capital expenditure. Jon Huntley, Explainer: Economic Effects of Infrastructure Investment, Penn Wharton Budget Model (June 15, 2021), https://budgetmodel.wharton.upenn.edu/issues/2021/6/15/economic-effects-of-infrastructure-investment.

Finally, the ARI’s structure elegantly optimized around dual-federalism, respecting traditional allocations of responsibility through state-level asset selection, but advanced national priorities through the matching program. In contrast, the IIJA arguably over-emphasizes delegation to administrative agencies, at least relative to prevailing norms; for instance, the Department of Transportation is responsible for allocating about half of new funding, totaling $274 billion. While there are logical arguments for greater utilization of federal capital for infrastructure,138See supra Part IV.

it does represent a departure from traditional divisions of responsibility, risking sub-optimal capital allocation and unnecessary jurisdictional frictions.139Kate Kelly, One of The Infrastructure Plan’s Biggest Winners is the Pavement You Drive On, N.Y. Times (Feb. 19, 2022) (citing Federal Highway Administration guidance on project prioritization that state officials felt “undercut them”), https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/19/us/politics/infrastructure-plan-asphalt.html.

II. Case Study: The MTA’s Tribulations & Restructuring Limitations